A delicate vision of transmutation wends its way through Chioma Ebinama’s rapidly growing oeuvre. It is there in the bees buzzing around the female figures extended hand in ‘Igba Gharie’ (ambivalence): has the woman decadently fallen asleep in the park on a sunny day as bees circulate the flower in her hair; or could something more dreadful have taken place? Perhaps those bees are inspecting the woman’s fresh corpse as her body returns to the soil.

Death, for Chioma, is not necessarily something to hide away from. Instead, memento mori is gently folded into her world. Hers is a community that is ready to embrace those confident enough to accept their fragility and become reborn into new forms informed by friends and lovers. Meanwhile, Ebinama’s Capitoline Wolf-esque figure in The Empress hints at the abundance of a collective. Rather than feed Romulus and Remus, this languorously floating figure suggests unexpected connectivity or communion with community and nature as it weaves its way through the cloudlike blue background.

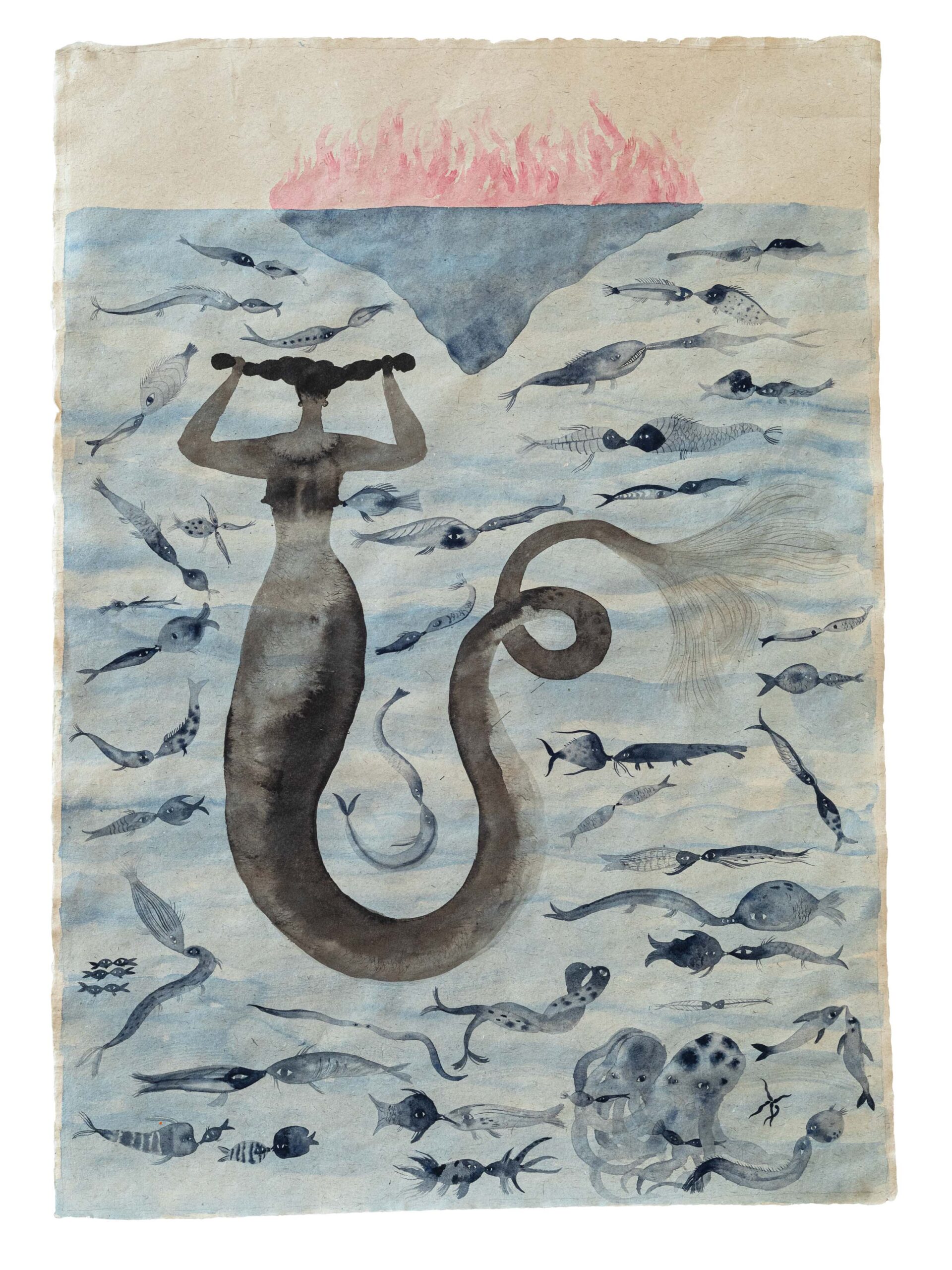

Making out while an empire burns, 2019

Chioma’s frequent depiction of butterflies, which survive for but a few days in all their stunning and ephemeral beauty, suggest further ways of embodying metamorphosis. As in Obi Uto (Joy) the insects’ wings appear full of life, ardently announcing their simultaneous beauty and a falsified danger to hungry birds and other potential predators. Vitality amidst mortal danger is there again in Feminine Figure, which depicts a female form surrounded by flames reminiscent of a volcano; but rather than expel fireballs, ruby red tendrils of blood ooze from the woman’s core. Is the woman setting herself ablaze in defiance of patriarchal conventions that shame menstruating bodies? Or is she literally inhabiting earth’s molten core that both gives life and violently remoulds the world with its searing heart?

In another of Chioma’s spellbinding works, Making out while an empire burns, a mermaid-like figure is suspended amidst anthropomorphised fish. It might have been conjured in the dream of a 15th century European artist commissioned to portray animals they had never seen in person. Numerous pairs of fish and a couple of octopi kiss as an upside-down glacier appears to be ablaze, suggesting the possibility to find and follow love as a presumably manmade empire burns to ash. Perhaps Ebinama is quietly suggesting that there is always liberation to be found, no matter the state of the world. After all, we always have our dreams to guide us, even in the most desperate circumstances.

Chioma is producing these and many other works within the broader context of an art market that feverishly clamours for Black figurative art in the on-going wake of 2020’s global Black Lives Matter movement. As if spending money on Black-produced art will seamlessly melt away a centuries-long legacy of global inequality. But rather than strictly adhere to a potentially lucrative path of depicting Black bodies in these and other works, the Athens-based Nigerian-American artist draws upon her childhood obsessions and unexpected adult pathways to showcase the specificity and richness of Black interiority. Chioma’s practice yields surprising results in what she articulates as the ‘[creation of] a freeway removed from the white gaze’, which, in turn, explodes rigid definitions of Blackness and other imposed identities.

Obi Uto (joy), 2021

Bliss, 2022

While the long-overdue expansion of art showcasing Black and brown bodies in all our resplendent beauty and humanity is a welcome shift, it also generates unease. In some cases, wealthy, often white-run, institutions and individual collectors purchase depictions of Black bodies that might feature in spaces where few people of colour, beyond domestic staff, frequent. Even if a handful of successful Black artists and artist collectives financially benefit in the process, this type of emerging reality risks cloaking business as usual and reproducing racial capitalist logics. Were it not for the profoundly painful personal and collective histories it unearths, it would all make for an incredible performance art piece, or an unsettling Jordan Peele film.

Feminine Figure, 2019

The beloved 01, 2019

Ebinama’s inward embrace forms a knowing critique of the labyrinth Black artists navigate in today’s post-BLM art world and intentionally shatters the narrow definitions of Blackness that have been foisted upon her. Suburban Maryland, where Chioma grew up in the 1990s and 2000s, contained at least three misidentifications: Black America frequently fails to understand African countries such as Nigeria, where Chioma’s parents are from, as places other than a mythical and deeply problematic ‘Hotep’ fever dream of kings and queens or a continent eternally afflicted by war and famine. Meanwhile, as Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche powerfully exposes in Americanah, many Nigerians can slip into a fractured understanding of the United States as the land of plenty or of narrow ‘Naija’ identity. Of course, each of these distinctions was and largely remains invisible to the white political context that forged BLM in the first place.

So, when a teenage Chioma fell in love with manga, she was cast as an outsider thanks to narrow definitions of Blackness imposed by the wider Black American community she was situated in, suburban Baltimore’s overarching white world, and her parents’ seemingly distant homeland. When Chioma does paint figures, their often-oversized eyes and dreamlike composition, which often suspends individuals, animals, and objects in space, recalls her loving embrace of the Japanese art form that first gave her permission ‘to be her own way.’ In manga, Black women can of course become multi-breasted figures that evoke fuzzy childhood memories of Falkor the floating ‘luckdragon’ from the 1984 film, The Neverending Story. In manga, Black women can quite naturally transform into human volcanoes that violently reconfigure and ultimately refresh the world through their lavalike menses.

amor mundi, 2021

Igba Gharie (ambivalence), 2021

Chioma’s practice also reflects how new creative pathways can emerge when Black Americans are granted the rare opportunity to build lives outside of the United States, where echoes of destructive settler colonial logics remain. Chioma’s Athens studio took shape after her pandemic experience uprooted her from New York. Her journey first took her to the safety of far-flung close friends in Seoul, London, and eventually Athens. Chioma discovered a deeper trust in herself that emanated through that period’s physical displacement, a trust that materialised through the support her community provided her. This realisation, in combination with the death that surrounded the pandemic, speaks through Chioma’s recent body of work; her dreamlike reminders of mortality draw from a Buddhist embrace of limbo or ‘bardo,’ the liminal state between death and rebirth.

Dreams, both the kind that our bodies generate as we sleep and our minds conjure in our waking hours, are perhaps the clearest manifestation of our inner worlds, which we can spend lifetimes discovering, reinterpreting and, at times, even embodying. Chioma’s works powerfully edify this often-hazy reality, similarly granting the viewer licence to turn inwards and explore what our own dreams might reveal to us. But rather than a solo process, community is integral to Chioma’s vision, which gracefully suggests that only through collective connection are these new selves revealed to ourselves and the world around us.

Pink World, 2022

All images courtesy of Maureen Paley.

A delicate vision of transmutation wends its way through Chioma Ebinama’s rapidly growing oeuvre. It is there in the bees buzzing around the female figures extended hand in ‘Igba Gharie’ (ambivalence): has the woman decadently fallen asleep in the park on a sunny day as bees circulate the flower in her hair; or could something more dreadful have taken place? Perhaps those bees are inspecting the woman’s fresh corpse as her body returns to the soil.

Death, for Chioma, is not necessarily something to hide away from. Instead, memento mori is gently folded into her world. Hers is a community that is ready to embrace those confident enough to accept their fragility and become reborn into new forms informed by friends and lovers. Meanwhile, Ebinama’s Capitoline Wolf-esque figure in The Empress hints at the abundance of a collective. Rather than feed Romulus and Remus, this languorously floating figure suggests unexpected connectivity or communion with community and nature as it weaves its way through the cloudlike blue background.

Making out while an empire burns, 2019

Chioma’s frequent depiction of butterflies, which survive for but a few days in all their stunning and ephemeral beauty, suggest further ways of embodying metamorphosis. As in Obi Uto (Joy) the insects’ wings appear full of life, ardently announcing their simultaneous beauty and a falsified danger to hungry birds and other potential predators. Vitality amidst mortal danger is there again in Feminine Figure, which depicts a female form surrounded by flames reminiscent of a volcano; but rather than expel fireballs, ruby red tendrils of blood ooze from the woman’s core. Is the woman setting herself ablaze in defiance of patriarchal conventions that shame menstruating bodies? Or is she literally inhabiting earth’s molten core that both gives life and violently remoulds the world with its searing heart?

In another of Chioma’s spellbinding works, Making out while an empire burns, a mermaid-like figure is suspended amidst anthropomorphised fish. It might have been conjured in the dream of a 15th century European artist commissioned to portray animals they had never seen in person. Numerous pairs of fish and a couple of octopi kiss as an upside-down glacier appears to be ablaze, suggesting the possibility to find and follow love as a presumably manmade empire burns to ash. Perhaps Ebinama is quietly suggesting that there is always liberation to be found, no matter the state of the world. After all, we always have our dreams to guide us, even in the most desperate circumstances.

Chioma is producing these and many other works within the broader context of an art market that feverishly clamours for Black figurative art in the on-going wake of 2020’s global Black Lives Matter movement. As if spending money on Black-produced art will seamlessly melt away a centuries-long legacy of global inequality. But rather than strictly adhere to a potentially lucrative path of depicting Black bodies in these and other works, the Athens-based Nigerian-American artist draws upon her childhood obsessions and unexpected adult pathways to showcase the specificity and richness of Black interiority. Chioma’s practice yields surprising results in what she articulates as the ‘[creation of] a freeway removed from the white gaze’, which, in turn, explodes rigid definitions of Blackness and other imposed identities.

Obi Uto (joy), 2021

Bliss, 2022

While the long-overdue expansion of art showcasing Black and brown bodies in all our resplendent beauty and humanity is a welcome shift, it also generates unease. In some cases, wealthy, often white-run, institutions and individual collectors purchase depictions of Black bodies that might feature in spaces where few people of colour, beyond domestic staff, frequent. Even if a handful of successful Black artists and artist collectives financially benefit in the process, this type of emerging reality risks cloaking business as usual and reproducing racial capitalist logics. Were it not for the profoundly painful personal and collective histories it unearths, it would all make for an incredible performance art piece, or an unsettling Jordan Peele film.

Feminine Figure, 2019

The beloved 01, 2019

Ebinama’s inward embrace forms a knowing critique of the labyrinth Black artists navigate in today’s post-BLM art world and intentionally shatters the narrow definitions of Blackness that have been foisted upon her. Suburban Maryland, where Chioma grew up in the 1990s and 2000s, contained at least three misidentifications: Black America frequently fails to understand African countries such as Nigeria, where Chioma’s parents are from, as places other than a mythical and deeply problematic ‘Hotep’ fever dream of kings and queens or a continent eternally afflicted by war and famine. Meanwhile, as Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche powerfully exposes in Americanah, many Nigerians can slip into a fractured understanding of the United States as the land of plenty or of narrow ‘Naija’ identity. Of course, each of these distinctions was and largely remains invisible to the white political context that forged BLM in the first place.

So, when a teenage Chioma fell in love with manga, she was cast as an outsider thanks to narrow definitions of Blackness imposed by the wider Black American community she was situated in, suburban Baltimore’s overarching white world, and her parents’ seemingly distant homeland. When Chioma does paint figures, their often-oversized eyes and dreamlike composition, which often suspends individuals, animals, and objects in space, recalls her loving embrace of the Japanese art form that first gave her permission ‘to be her own way.’ In manga, Black women can of course become multi-breasted figures that evoke fuzzy childhood memories of Falkor the floating ‘luckdragon’ from the 1984 film, The Neverending Story. In manga, Black women can quite naturally transform into human volcanoes that violently reconfigure and ultimately refresh the world through their lavalike menses.

amor mundi, 2021

Igba Gharie (ambivalence), 2021

Chioma’s practice also reflects how new creative pathways can emerge when Black Americans are granted the rare opportunity to build lives outside of the United States, where echoes of destructive settler colonial logics remain. Chioma’s Athens studio took shape after her pandemic experience uprooted her from New York. Her journey first took her to the safety of far-flung close friends in Seoul, London, and eventually Athens. Chioma discovered a deeper trust in herself that emanated through that period’s physical displacement, a trust that materialised through the support her community provided her. This realisation, in combination with the death that surrounded the pandemic, speaks through Chioma’s recent body of work; her dreamlike reminders of mortality draw from a Buddhist embrace of limbo or ‘bardo,’ the liminal state between death and rebirth.

Dreams, both the kind that our bodies generate as we sleep and our minds conjure in our waking hours, are perhaps the clearest manifestation of our inner worlds, which we can spend lifetimes discovering, reinterpreting and, at times, even embodying. Chioma’s works powerfully edify this often-hazy reality, similarly granting the viewer licence to turn inwards and explore what our own dreams might reveal to us. But rather than a solo process, community is integral to Chioma’s vision, which gracefully suggests that only through collective connection are these new selves revealed to ourselves and the world around us.

Pink World, 2022

All images courtesy of Maureen Paley.